People I Owe: My Dad

I’ve avoided writing this “people I owe” post for years out of pure fear. How can I possibly “do it right?” I felt some of the same anxiety writing about Stan Klotkowski, Jeanie Omelenchuk, Clair Young, and Mike Walden but not like this. Deep down I’ve also been worried about the very real fact that Stan, Jeanie and Clair all passed away within months after I wrote about their impacts on my life. As far as I know none of them even were aware of my heartfelt gratitude. Mostly I’ve avoided this “people I owe” because it is a family member and hence any recognition contains the complex interactions that the designation of “family” creates.

In recent years I’ve participated in a number of leadership training curriculums where part of the interaction was to share with the group about someone who had had an impact on my leadership capacity or “leadership legacy.” I was repeatedly chagrined and surprised when teammates listed their father as one of their leadership icons. For these people their father had been a person who exemplified “typical” leadership characteristics – volunteering, military duty, leading charitable efforts, roles in community organizations and chairing change efforts. Inevitably they seemed to be extroverts, social organizers, “pillars of the community”, outspoken, brave, members of committees.

With absolutely no judgment upon my own father he simply did not fit this model. Meetings, committees? No way, my father – a strong introvert - avoided even social gatherings like family reunions. So I put this aside and found stereotypical leader archetypes from other walks of life to share as my influences – Jack Rooney or Mike Walden for example, people who had been pinnacles of traditional top-down leadership, with “presence.” Deep down though, part of me thought, “If my dad wasn’t a leader, what was he? He certainly impacted my life…”

With maturity comes wisdom and perspective and with perspective comes the realization of the gifts of leadership my father gave to me.

1) Opportunity: growing up a series of opportunities were, in some cases, literally put at my feet. Tennis lessons, swimming lessons (I'll circle back to these two), piano lessons, french horn lessons. The there was my orange crate Kmart bike with the banana seat, a first round Hobie skateboard, hockey skates, downhill skis, cross country skis, running shoes, hiking boots, camping gear – my life as a kid in the Coyle household meant that almost every weekend and many weekdays were filled with outdoor sporting activities. Gladwell and others have written about the 10 year/ 10,000 hour rule, and in hindsight, I probably rode more miles on my bike the summer when I was 8 years old than any other 8 year old on the planet – by my count we did 13 century / half century rides. I skied the Pinery in Canada, Great Bear up north and of course the Wabeek golf courses. I played hockey on our frozen lake, raced BMX weekends and weekdays winning more than 200 trophies. At one point when I was 11 or 12 I was State Champion in road cycling, track cycling, BMX racing, cross country skiing and skateboarding all the same year. I was horrifically competitive, crying if I even came in second place. But that part, the ridicululously competitive part appears to be something I was born with that my father managed with grace.

2) Being There. Did my father ever miss a game, a meet, a performance? Maybe he did – I guess in the grand scheme of life he must have. That said, I scratch my head and can’t come up with a single instance or memory of him not being there. Not once, ever. I have no notion or emotional impression of a repeated theme from movies, stories and books of “daddy wasn't there/didn't care.” 4am practices on Sunday morning after an hour’s drive to Flint Michigan or a Saturday evening soccer game? A painful band concert or choir rehearsal? Practices for 5 sports and music every single day of the week in disparate locations around the country for decades? He was always present, always supportive, always driving - the car that is.

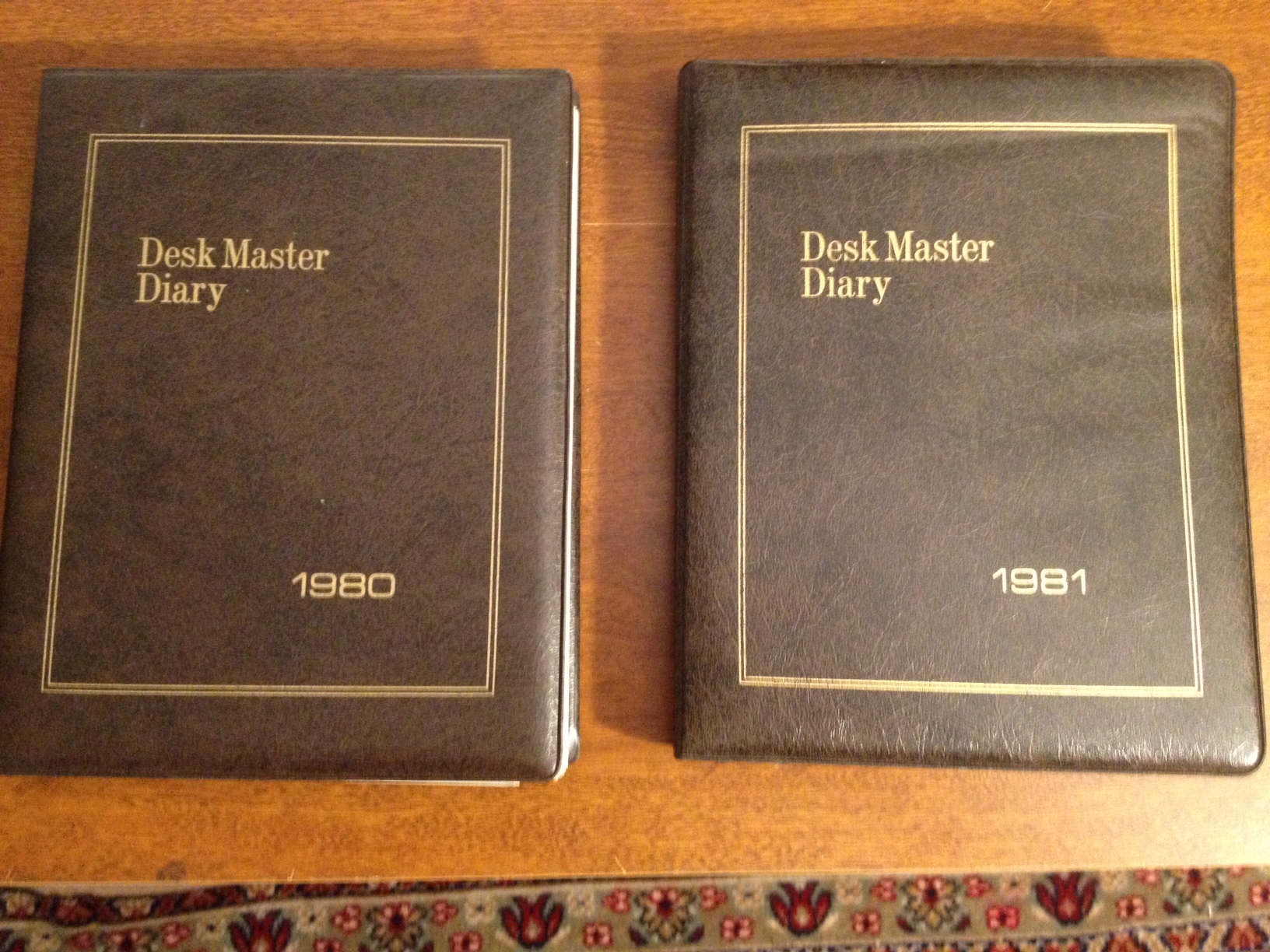

This is a picture of set of two day planners that capture calendar entrees from the years 1980 and 1981. Almost every single page of those years have a journal entree of a practice or race or often two entrees. When we traveled for a competition, the mileage was sometimes noted. The 1980 journal shows that we traveled in excess of 52,000 miles for competitions. With my own daughter I am daunted by this form of servant leadership. How can I EVER live up to it?

The following entries give about 6 weeks of my summer as an 11/12 year old. In the first below you can see practices each evening and then a 100 mile century ride in Michigan on Saturday (called Helluva Ride) followed immediately by a bike race in Connecticut on Sunday (drove all night? we NEVER flew anywhere)

The next week was spent racing in Wisconsin. Here's my first Superweek races - at first getting beat by Steve McGregor... Sadly this year is the first year in 33 years that I won't be racing superweek as the series closed down at the end of last season.

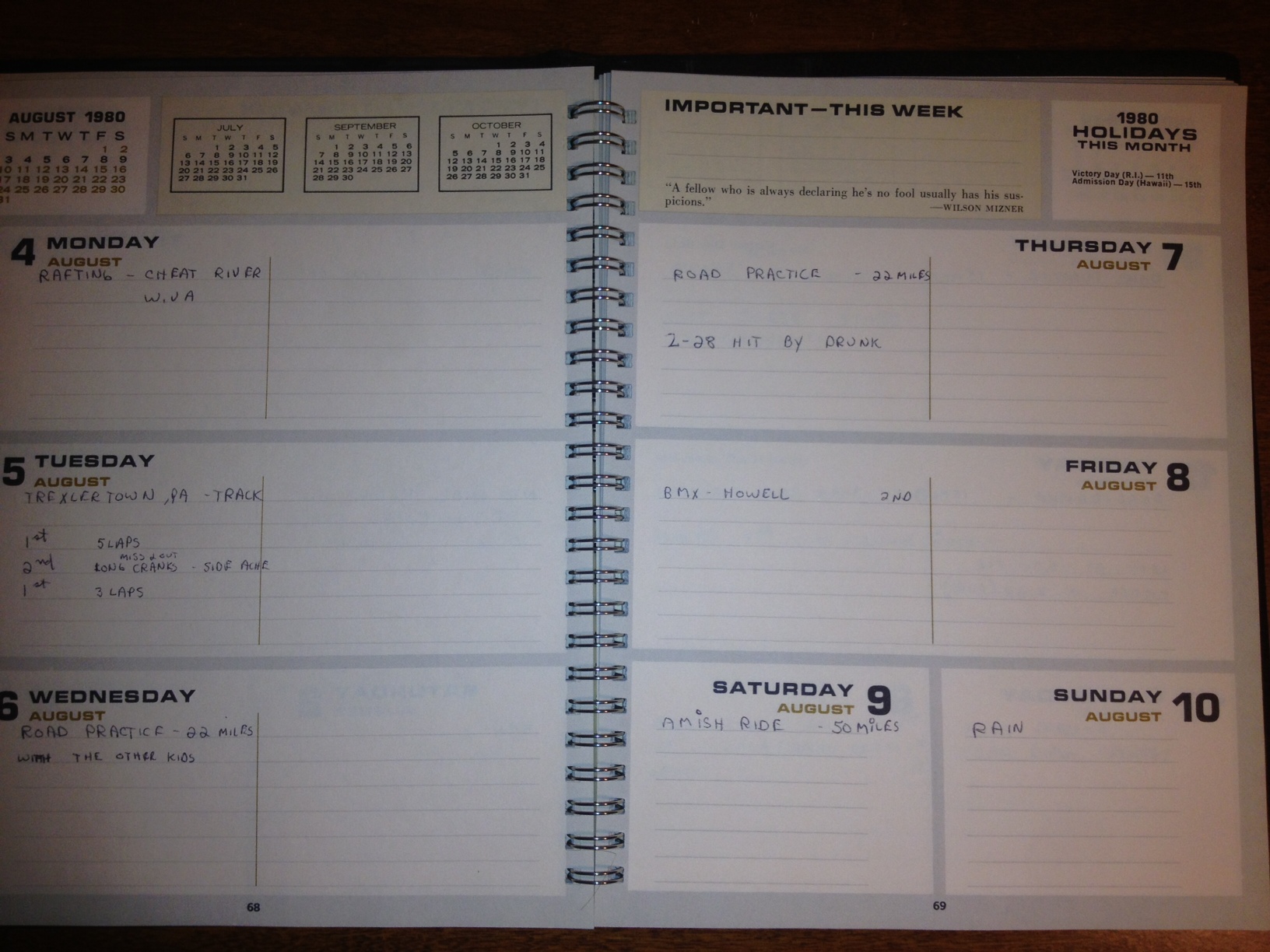

The next week: in one week we went white water rafting in West Virginia, then raced on the track in Pennsylvania, did a few practices and a BMX race in Michigan, then another century ride in Indiana (the Amish ride). It then rained on Sunday - perhaps we were relieved...

The next week: in one week we went white water rafting in West Virginia, then raced on the track in Pennsylvania, did a few practices and a BMX race in Michigan, then another century ride in Indiana (the Amish ride). It then rained on Sunday - perhaps we were relieved...

I remember this week clearly - we had a Camero Z28 that got hit by another car just before our plans to drive it out to Arizona and California (and then sell it to pay for the trip) I got crushed at road nationals coming in 4th, but the next day won two different BMX races in AZ.

I remember this week clearly - we had a Camero Z28 that got hit by another car just before our plans to drive it out to Arizona and California (and then sell it to pay for the trip) I got crushed at road nationals coming in 4th, but the next day won two different BMX races in AZ.

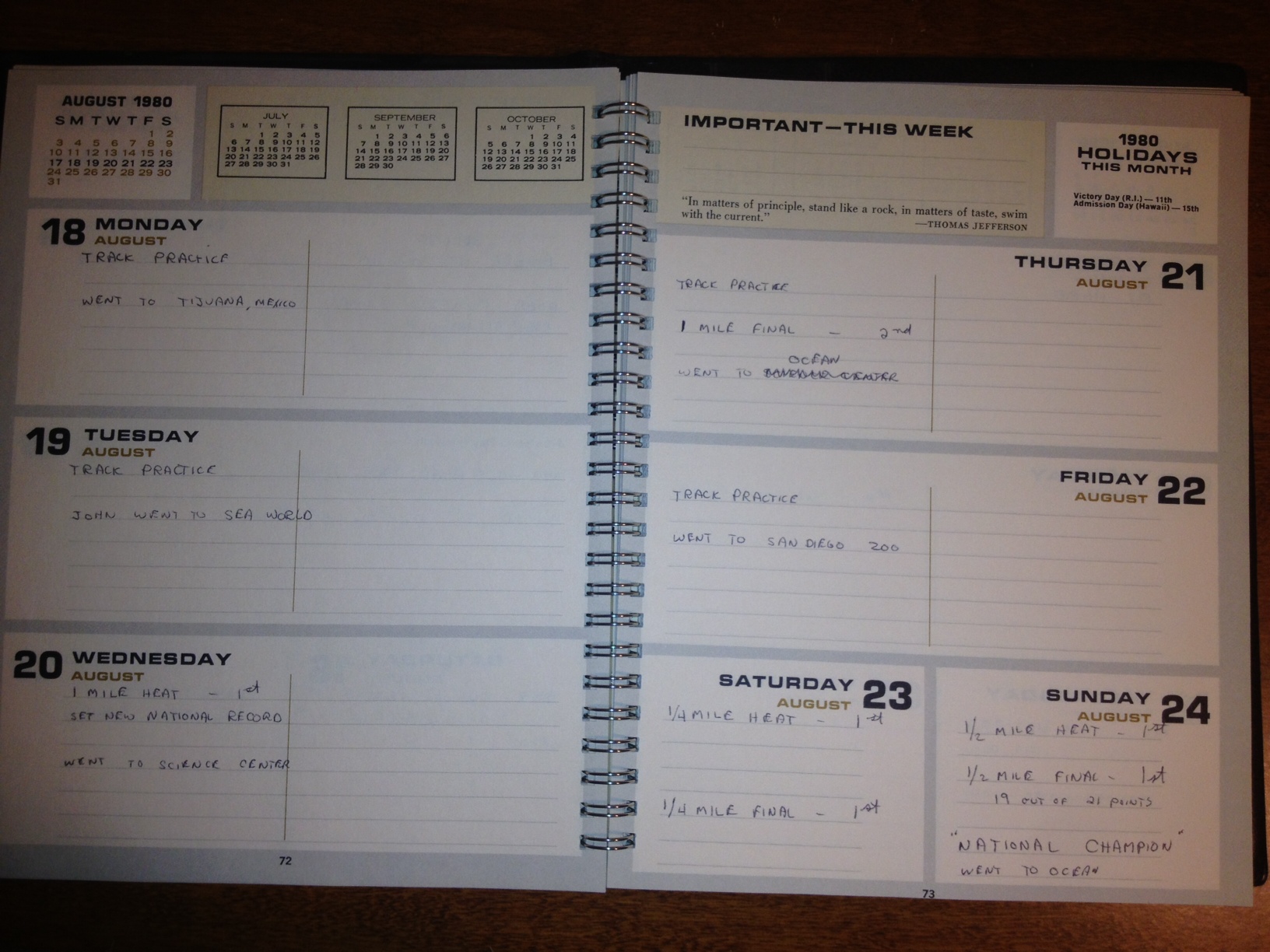

The following week I went to Tijuana on my 12th birthday (August 18) and I became national champion for the first time in San Diego, CA. (See lower right)

The following week I went to Tijuana on my 12th birthday (August 18) and I became national champion for the first time in San Diego, CA. (See lower right)

Here's a few pictures from the 1980 nationals:

Here's a few pictures from the 1980 nationals:

3) Belief. Perhaps the greatest gift of a leader to a follower and a father to a son, my father gave me 100% unequivocal belief. Belief begets hope, which is the greatest power in the universe. A skinny, redneck, hard-to-tame kid managed to harness a potentially deadly over-abundance of energy through one and only one force – that of belief.

My father treaded that incredibly narrow tightrope between sharing the destructive power of reality “you’ll never be good at this” and the equally damaging artificiality of the fake, “You’re the best, it was the referees fault”. At its core, my father anchored belief in one of my real strengths: “the gift of acceleration” as he called it. Little did I know how physiologically resonant was his evaluation of my talents. To be clear he didn’t say much. We didn’t have big inspiring coaching conversations, but when things went poorly he had a reason that provided a balance of opportunity for me to improve with that of hope.

How did he learn it? Why did he do it? To be clear, my father did not appear to have any kind of role model from his own parents. Generally ignored as a late addition to a family with an overachieving sister he certainly received little support from his own parents. He could be brittle and sadly our closeness created a separation with my sister that exists to this day. Conversely he also managed to avoid the mold of the “vicarious living through your offspring” parent often seen in competitive sport. He was, as I’ve learned the phrasing recently, “committed, but not attached” to the outcomes of my activities. Deep down I want to believe he just enjoyed the ride that my feeble singing voice, lousy French horn playing, decent academics and powerful but skinny legs provided. Maybe it was a simple as that – I wasn’t much to look at, didn’t come from a legacy or pedigree, but when my legs hit the pedals or skates, a resonant hum took over – at least for few seconds – and it was surprising coming from such an average kid. I was, when it comes down to it, pretty fast. Watching my daughter in sport now, I "get it" - it is a joy to watch when she's fully committed.

Time for a confession: what my parents may or may not know is how truly competitive I was as a child. If I wasn’t immediately good at something, I immediately wanted to quit, and in two cases at least, I was secretly successful. When, as a young boy, I was given weekly swimming lessons for a summer paid for by good parents, and on the first day found myself cold and floundering against more accomplished swimmers, I quit. Each week thereafter, after getting dropped off, I went and hid in the woods for 90 minutes rather thane “lose.” I never completed another lesson. Sadly the same was true for tennis lessons: after the first one I hid and skipped all of those as well. Sorry mom, sorry dad.

I am a father now. I struggle constantly with the balance of “over-involvement” that has come to characterize parenting today. When I was a child, if I fell down they didn’t rush out and soothe me, but if I fell and I was actually hurt they did. They didn’t pretend every performance was awesome, but did acknowledge that every tremendous EFFORT was awesome. But they also didn't miss a single program.

What is leadership if not the ability to help someone else achieve all that they are capable of? Like all humans my father had and has his flaws, but when it comes to his role of a parent to a spastic, competitive, sensitive kid, he was near perfect in helping me tap into my limited strengths. Literature, movies, and deep conversations seem to often turn to "daddy doubts" or a sense of abandonment by parents. From a distance it is pretty clear: I'm a limited talent athlete, decent student, poor musician who has been granted a life of adventure and accomplishment that is founded and grounded in the love of two parents who managed to give at least one of their offspring the feeling of complete and total unconditional love.

I have never, and I mean never ever, doubted the complete love and support of my father. It is so much of a given that it has been completely taken for granted. When it comes to my parents and my father I doubt for nothing. Nothing needs to be said, nothing needs to be done, it just exists. We sometimes go without talking for periods of time that (I realize now) are selfish of me. But no experiential time passes between conversations and meanwhile I'm naturally applying everything I've learned to the relationship with my own daughter, which, by the way, is a beautiful and "near perfect" relationship. I didn't even have to think about it really - I just needed to follow the directions I've been given.

In hindsight, we never talked much, my dad and I. We just did things, experienced things. So perhaps for that reason I probably never got around to thanking you dad. Thank you for the gift of experiences and slowing down time together (did we really do all that!?). Thank you for always, always being there. Most of all thank you for believing in me. Because you believed in me, I believed in me. My life has become a wondrous adventure through time, filled with incredible experience thanks to your unshakeable belief. It is the foundation that serves me every single day. Oh, and sorry about the swimming and tennis lessons.

Happy Father's Day dad. I love you.

-John, 6/16/2013