Race Your Strengths! Vol. 2

Colorado Springs, July 1990 continued…

Tests #2 & 3: Body Fat & VO2 Max

Over the coming days I eventually recovered from that initial breakdown from the heavy training and started to rejoin the competitive fray in the workouts. Sprints, jumps, reaction drills, low walks, lunges, hamstring curls, hip sleigh, bike rides, inline skating, weights, circuit training, “fartlechs”, stairs, plyometrics – we did it all and after a couple of weeks I was more fit and it was time for testing. Meanwhile, one particular workout we did stood out in my mind: on the infield of the track on the astro-turf we had to lay flat on the ground, facing away from a ‘runner’ positioned the same way 15 feet away and upon a clap were supposed to jump up, turn around, and try and catch our prey. I was quite good at this – at the signal I bounced up rotating in air and was running as soon as my feet hit the ground. I often caught my “prey” before they even started running.

I tried to selectively view this little area of strength as a sign of my athletic prowess (I still didn’t really understand the granular nature of strengths and I wouldn’t for more than a decade.) Instead I used these “crutch moments” to shore up my resolve on the days to come. As it was many, if not most, of the other workouts and tests seemed to go a different direction…

Over the next few days we were to undergo the following ‘tests’: 1) body fat (through calipers,) 2) VO2 Max, 3) Max squats, 4) Vertical leap, and 5) Max power output (watts.)

Body fat testing took 2 minutes. I had always been thin and lean so I didn’t give it much thought. That is until the “hmmm” of the sports doctor and assistants. They told me my body fat composition: 10.2%. It meant nothing to me – until I found out I had the second highest of any male at the camp, and that Bonnie Blair’s body fat (at 9.8%) was less than mine (men typically have considerably lower body fat than women - the general ranges for elite athletes are 2-6% for men, and 10-13% for women.)

Test #1 – Hard Training: Failure

Test #2 – Body Fat: Failure

Earlier that day we had been given our start times for the VO2 test to take place over that afternoon and all the next day. Everyone seemed nervous and stressed, but when I asked someone about the test they said, “don’t worry – it’s a cycling test so it will be easy for you – but it is hard!” Meanwhile a buzz was going around campus that a superstar young cyclist was there by the name of Lance Armstrong and that he would also be testing. As a long time cyclist I had never heard of him and did not give it much thought.

It was late the next morning when it finally came time for my VO2 test. I remember riding my bike across the extended campus of the Colorado Springs Olympic Training center – down the hill from the dorms, past the rubberized track and into the maze of structures in between the track and the cafeteria. This series of low outlying buildings (former barracks) ran in neat rows and were completely nondescript – each one looked like the other. The light outside was crisply brilliant as I locked my bike up and entered the white fluorescent lights of the hallway and plastic tile floors into a small waiting room where I changed into my cycling gear.

Shortly thereafter one of the other skaters came down the hallway into this small room to change back into his street clothes. He was shiny with sweat and looked grey. “Good luck,” he said, “that sucked.”

I had no idea what I was in for.

Dressed and ready, I followed a lab assistant down the white tiled hallway, my cleats clicking and sliding as I navigated a small set of stairs with those wooden handrails and aluminum scuff guards sprinkled with shiny specks of stone on the toe of each stair. I clicked my way safely down and into a room full of equipment – all centered around a stationary bike. There were a half dozen people in the room, most were wearing white medical garb.

One of them approached me and encouraged me to get set up on the bike in the middle of the room and let me know that they would be attaching some monitoring equipment and asked me to remove my shirt.

I climbed onto the contraption and all at once the room became a hive of activity: extended fingers pushing buttons, cords clicking into machines, and the shiny steel mandibles of various instruments gathering my vital signs. One attendant suddenly and unapologetically began to slather a clear cold gel on my chest while another began attaching black backed sensors to the viscous goop. A third attached electrodes to the sensors, while a fourth pried a finger loose from the handlebars, and then, without asking, stabbed me in the finger with a pin she had just swabbed with alcohol, greedily milking the blood out of it into a tiny glass test tube and then disappearing into the hallway behind the machines.

A web of wires from the machines around the room were then clipped to the electrodes as though I were ready to be lit up like a wedding gazebo. Like a maggot writhing in a spider’s web, I was turned, prodded, and poked. Finally the doctor approached, consulting his shiny black metallic wristwatch and asking, “are you ready?” It was clear that he wasn’t waiting for the answer and he nodded to yet another assistant.

“This may feel a bit awkward” she said as they fitted an ugly contraption from an orthodontic patient’s nightmare to my head – crisscrossing straps pressed into place over the top of my scalp supporting a mechanism that that contained a length of a thick plastic tubing.

I didn’t mind it so much until they rotated the large tube into place in front of my lips and then said “open” and then jammed it backward into my mouth. My jaws were ratcheted open like in a dental X-ray and then left that way. Another intern brought over what looked exactly like a long, stretchable, clear hose from a vacuum cleaner and attached it to the other end of the tube in my mouth. The far end of the 15 foot tube draped to the floor and then rose again to where it was connected to one of the many large machines in the room.

Even as my jaw began to ache from being pried so wide, the doctor said again, “ready?” and turned away before I could answer. He wasn’t talking to me. I swear I heard his mandibles click as he walked away - or perhaps it was just the clamp of his clipboard. Actually, it was the positioning of an ordinary clothespin on my nostrils to keep me from breathing through my nose. My claustrophobia reached its max and I had to fight the gag reflex. It got worse when I considered that others had had this tube in their mouth, and others had had the gag reflex, and perhaps that taste and smell….

Fortunately I was distracted by the start of the test and all the assistants and lab coats disappeared into far corners except for one of the younger girls in the room who advised me, “Just maintain 90 rpms – we have set the resistance at 175 watts.” “In two minutes, we’ll increase the watts and rpms, and continue to do so until we get a reading at your max.”

Translation to the maggot, “we are going to roast your fat white body on this spit until you die or explode.”

Still, 90 rpms at 175 watts wasn’t too bad and the 2 minutes passed with only a small level of effort and the warming of my limbs and lungs. If it hadn’t been for the jaw pain and consciousness of all the dangling cords swaying with my body I would have been comfortable.

At two minutes the intern was back, turning the dial of resistance and informing me, “You are now at 200 watts of resistance – please increase your rpms to 95.” At the same moment the vampire with the pin suddenly stabbed a second appendage and began sinuously squeezing that finger to extract more blood. I would have said something – except for the tree trunk in my mouth.

I pedaled and entered that middle realm of work on the bike that is satisfying. I monitored my rpms and my heartrate and watched it climb from the 140’s to the 150’s into the 160’s. I began to sweat a little which didn’t bother me. I began to drool a little, and that bothered me immensely. I followed the spit as it stairstepped down the accordion layers of the tube and then followed the hose back to the machine, then the machine to the heavy black cord, and the heavy black cord to the outlet in the wall. I began to consider the physics of electricity – voltage and amperage – and the conductive properties of water. This was all rational cover for my building claustrophobia. I pedaled and tried not to panic.

2 minutes later and 4 minutes into the test, my little intern reappeared and I cast about for the vampire as well. Sure enough she materialized at the same time, and even as the soothing voice began to announce the next level of torture (225 watts, 100 rpms), my middle finger was extended, stabbed, and milked for blood in one swift and fluid effort by her sidekick.

225 watts is hard. It is not killer by itself, but what begins to make it hard is the idea of what was to come – a never ending ladder to hell – more watts, more rpms, and more pedaling. As the effort increased, I was starting to be able to move beyond staring at the wires and machines and even the gigantic snorkel in my mouth. I finished the 6 minutes, working hard, and was beginning to breathe quite heavily. My pulse was in the mid-170’s.

The intern began her dulcet announcement, “250 watts, 105 rpms” and in complete synch I held out my still immaculate index finger for the pin and the blood and the test tube. The vampire scooted away with a flap of her gown.

Head down, I began to work in earnest and watched the gleaming sweat on the hair of my forearms as I swayed in the saddle and worked through the 2 minute interval. I was beginning to labor now, my breath coming faster and faster, pulse climbing to the mid 180’s.

At 8 minutes I was sweating and breathing hard and convinced I was almost done.

“Halfway” said the white coated intern smooth but emotionless, “shoot for 16 minutes.”

16 minutes?! NO FREAKIN’ WAY! I thought as she changed the resistance to 275 watts and asked me to increase my rpms to 110. I decided to shoot for finishing this 2 minute interval.

It got hard – really hard. My lungs worked like bellows, and my thighs began that burn from lack of oxygen. Head down I had lost all contact with the tube and the vampire and the lab coats except for a sudden realization that they were all drifting back into the place. My suffering was a magnet pulling them in, and the harder I worked, and the more my heart rate climbed, the closer they got, and the more they talked.

My pulse entered the 190’s and then the low 200’s. I was pulverizing the pedals and the air in my lungs began to burn. Somewhere around this time, the vampire began slashing my fingers at 30 second intervals and I stopped caring which finger had holes in it already. Sweat coursing off my body, and rivers of saliva draining into the tube I finished off the 10 minutes and it was time, again for an increase.

This time it was the doc himself: “300 watts, 115 rpms – from here on, the rpms will stay the same – continue” and I felt the resistance increase yet again. The resistance was less of a factor than the increase in rpms. 115 rpms felt like a hurricane for my tired legs and I was certain I would last less then 30 seconds.

The group that had gathered sensed this internal negotiating and one said, “make it 60 more seconds – you can definitely make that.” I looked up and noticed my heartrate – 210 beats per minute. I determined to make it the full 60 seconds and did – but they were ready, “Make it 30 more seconds! You can do it!” They pressed closer and in hindsight I wonder what kind of mindset revels in such suffering. I made eleven minutes and 30 seconds and they said “30 more seconds – make the 12 minute mark!”

By now my legs were gigantic burning red balloons and my lungs were embers. Still I struggled on and when my rpms dropped below 115 they poked and prodded and I returned to 115 on the monitor.

Twelve minutes arrived and I was intending to quit, but suddenly there were 5 faces in front of mine and none were relenting. “You can do more than this! You must continue!” and the doctor’s voice droned on, “325 watts, 115 rpms.” The vampire continued to collect her blood from my bloody fingertips without the pin as we’d given up trying to close up the holes in between. A drop fell from my fingertip.

So I gave it my all and focused on making 30 seconds as the room pinwheeled around me and my pulse climbed to 215. I made it and still they pushed “30 more!” They were screaming now, “Go! Go! Go!” Knees flailing, lungs flapping like bellows I continued and the wheezing and rasping sounds of my death rattle began. But still I made thirteen minutes and they convinced me to shoot for 13:30.

At thirteen minutes, thirty seconds my body began to implode. My heart rate had reached 217 beats per minute, and by the excited squeals of the vampire I determined that the lactic acid levels in my blood had also reached significant levels. I tried to follow directions from the room to make the fourteen minute milestone, but 9 seconds later my legs stopped turning. 13:39.

They all congratulated me in a seemingly sincere way, so I assumed I had done well, and that 16:00 was the “holy grail” and that I had gotten close. One mentioned that I had one of the highest lactic acid levels they had measured as well. I asked what that meant, and she said, "You are good at suffering." Great.

I could barely crawl down from the bike after they removed the tube and all the wires and with considerable effort grabbed my shirt and walked back down the hallway to the dressing room. I was gray. Along the way I passed a fresh faced cyclist I didn’t know by the name of Lance Armstrong on the way to his test.

I dressed and headed back to the dorms. After a convivial dinner with my roommates and other skaters I received a manila envelope under the door with my test results.

I tore it open eagerly. I had been congratulated. The ants and spiders had been genuinely interested. I had worked harder than most humans are capable of conceiving and suffered to the point where I nearly passed out. I had been 10th in the world the prior year at age 21 with minimal training. I expected results that matched my talent, my effort and my prior performance.

Instead I received a chart that showed my result compared to the average team member.

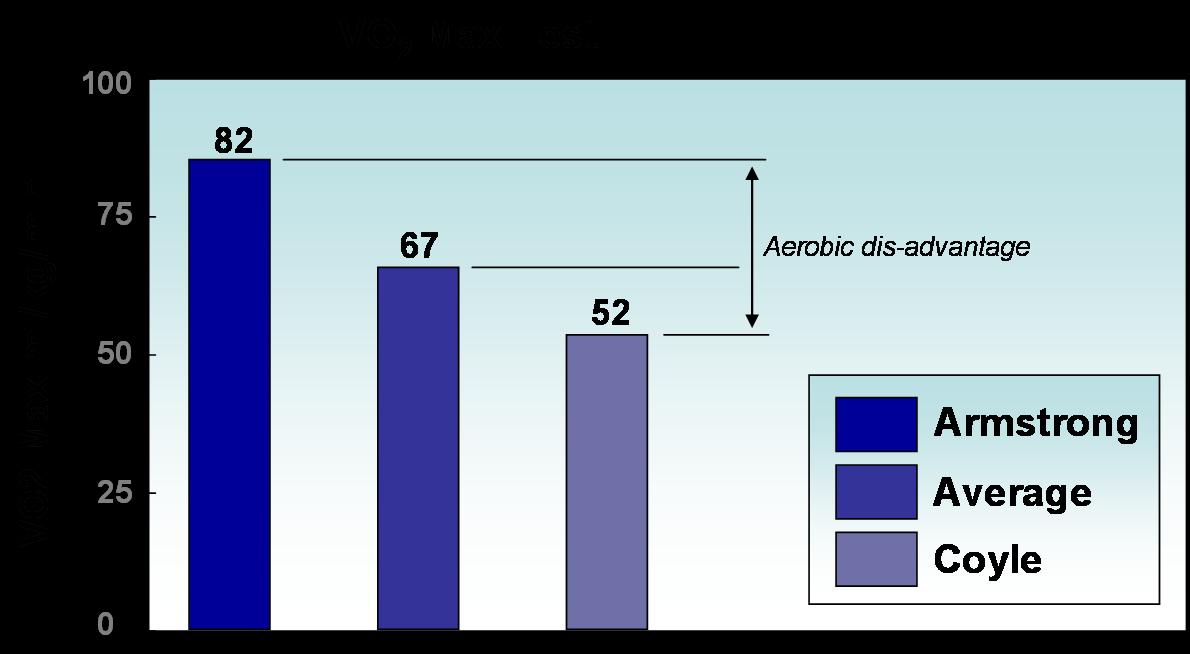

According to this test, I had the worst VO2 of the entire team – and this was a test the coaches had suggested was the single greatest predictor of success in our sport. Later, I learned that Lance Armstrong had survived 26 1/2 minutes and maxed out at 500 watts. When I was done, he was only halfway – and it only got harder…

Test #1 – Hard Training: Failure

Test #2 – Body Fat: Failure

Test #3: - VO2 Max: Failure

If I knew then what I know now, I would have realized that this was a true weakness for me – that I lacked the kind of “steady, building” aerobic capacity that the test was measuring for. In fact it wasn’t until the last few years that I realized how specific strengths are and how even tests like the above really can’t accurately capture reality. Let me put it another way – according to the test above, my aerobic threshold at my prime was around 275 watts. Yet I constantly finish races that require an AVERAGE watts of 330 or so just to finish – for a 2 ½ hour period and can sustain watts of 600+ for 4 - 5 minutes, and. How is this possible.?

It is possible because I can produce multiple 2-5 second pulses of 800 watts with 5-10 second “rests” of 150 watts over and over again.

But this test failed to measure these kinds of variations – it only measured steadily increasing watts – like the kind required to climb a mountain or timetrial against a headwind. For the record, I cannot climb, nor fight a headwind - though I spent many years trying.

The test was right. But I disavowed it from the beginning. “Can’t be right,” I thought and began a series of denials that stayed with me for the next decade. This despite the fact that the other 2 times I took the test I also scored exactly a “52”.

These results really should not have been a surprise. That said, I think many athletes, myself included at the time, try not to think about their failures, or if they do, do so in an emotional, rather than a clinical way. With any understanding of my capabilities at all, these tests would have been a mere reflection of my reality. Here’s an example.

Flashback: in the summer of 1985, while riding for the 7-11 Junior Development Team, I was required to ride in the Red Zinger Mini Classic/Junior National Tour – a 10 day stage race through the mountains of Colorado.

I quickly proved I was incapable of climbing and proceeded to get dropped on every mountain stage race at the bottom of the first hill. I was completely confused – I had won 11 races in a row prior to heading out to Colorado – against many of the same riders – how could this be?

I started to understand when, on the same day, I placed last in the Vail Mountain uphill time trial, right after winning the field sprint and 4th place in the Vail Criterium. Someone else had to tell me though: “Dude, you just can’t go UP!”

The next day was a long road race – from Copper Mountain to Leadville, with a series of climbs after a flat start. By then the entire peleton realized I couldn’t climb, so my teammates and the field conspired to let me breakaway on the first 7 mile flat section. By the time we hit the first climb, I had a 5 minute advantage on the field – one of the only breakaways of my life. Rather than attesting to my abilities, this was a testament to my well known inability to climb – the entire field was so confident I couldn’t climb, that they rode about 15mph for the first 7 miles to let me get away and then chase me down on the ascent.

Sure enough, a few miles into the long, heartwrenching climb, they caught me. I sped backward through the 100+ member field, and then fell out the back a half a minute later.

Then, the girls caught me. Sadly, they had started 5 minutes after the boys, so I had squandered not only my 5 minute lead on the boys field, but had lost the difference to the women’s field.

I managed to stay with the leaders of the girl’s race, and finally entered the high altitude flats of Leadville and the finish stretch. I’d like to say that I coasted in with the girls with my head down, but I CAME TO RACE and blasted out of 15th position with 200m to go to destroy the women’s peleton in the sprint.

In his great book "Now, Discover Your Strengths" written 15 years later, Marcus Buckingham summarizes natural strengths as follows:

Each person’s talents are unique and enduring: “The definition of strength is quite specific: consistent near perfect performance in an activity.”

For the last 32 years of my life, I have never been able to climb, or time trial, or break away, or win long sprints. What I have been able to do nearly perfectly is to win short sprints on technical courses in crowded conditions. Add a small hill prior to the finish and my results almost always include a spot on the podium.

Damn, this would have been nice to know back in, say, 1985….

Next up, Tests #4 & 5: Vertical Leap, and Max Power Output