Race Your Strengths! Vol. 3

Next up, Tests #4, 5, 6: Max Squats, Vertical Leap & Max Power (Wingate Test)

Flashforward - 1 year to 1991. Back at the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs for another camp. The Junior World Cycling Championships are taking place at the same time, and I catch up with cycling friends Jessica Grieco and George Hincapie. Jessica and I spend a good deal of time together and another cyclist I only know by name, Lance Armstrong, notices.

After the Junior World Cycling Championships were over, I attended a house party near the Olympic Training Center (OTC) with skater and Olympic silver medalist Eric Flaim and some of the other skaters and hooked up with George and Jessica and met many of the other cyclists. At one point mid-way through the evening, after a long discussion with Jessica, I was motioned outside by a “minion” of Lance’s. Lance was only 19 but already had assumed command of the junior ranks. He was waiting for me out front of the house and asked me if I would walk and talk with him. It was very movie-like. I said, “sure.”

We walked to the curb, and then sat down. He then proceeded to ask a series of targeted questions about Jessica (who was not without her charms) with that same, now famous, hawk-like stare. He started with, “How did you get her?” I explained that we were just friends and that we were not romantically involved. He immediately followed up with “Well, how can I get her?” and then asked a series of very specific questions. “What kind of music does she like? What does she read? Does she wear perfume? What are her hobbies outside cycling? Is she smart? What’s her favorite subject in school?” and then again, “How can I get her?”

I can imagine Lance and Chris Carmichael planning his comeback in much a similar fashion, “how can I get tour #8?”

I tried to be helpful, but found it all a little bit like a science project and wanted to ask, “what does, ‘get’ mean, exactly?” but I didn’t. Later I saw him talking to Jessica with some of the same intensity – though he did bother to smile and laugh.

Back in Colorado Springs, July 1990.

Just two days later and the testing continued. The next test was Max Squats: the ability to lift heavy objects dangling from a metal bar resting on your shoulders from a compressed position. I was happily not dead last. In the intervening weeks I had gotten better at the exercise and had moved up to being able to lift three 45lb plates on each side of the bar – for a total of 315 lbs – my one repetition max.

DJ (Dan Jansen’s preferred nickname) maxed out near 600 lbs.

Next we tested vertical leap. Honestly I was expecting to do really well. But the rules were strict. Bend slowly as deep as you wish, and then jump as high as possible swinging your arms and hands up over your head, and then using the tips of your fingers to swat at rotating height markers. I found my jumps lackluster, empty – as though I was missing something – like I almost wanted more weight on my shoulders. What I figured out now, writing this 18 years later is that what I really was missing was resistance or compression. With no real load (like skating a short track corner, or the gearing on a bike) my legs and synapses were just average. My results put me squarely in the middle of the pack. Conversely, over the years whenever we did a typical set of hurdle plyometrics - 10 hurdles set back to back at their highest setting (around 4ft), completed by doing knee to chest jumps, one to each hurdle - I was able to fly high. But I needed that compression of my weight returning from the prior hurdle – I needed that tension.

This came into stark contrast with another jump workout one summer in Calgary where my very specific, granular strengths came into play. The track team at U of C had built a series of tall steps – almost leaps – 2 feet between each block, 6 steps total, taking you up 12 ft vertical by the final step, and ending with a foam lined landing pit beneath the steps. The challenge was to run down a short lane, bound up each large step and then launch into the air over the pit, landing safely in the foam – sort of a combo between a “hop-skip-and-jump” and the high jump.

Most everyone else accelerated to the steps, and then decelerated up them, thumping up each step and then sailing sideways into the pit. But this setup really was perfect for me - - I was like an astronaut on the moon - each terrace had my feet on springs and my speed and vertical speed increased with each bounding step – by the last few stairs my feet were hammering the wood like jackhammers and I would launch into orbit, legs and arms wind-milling in slow motion during the extended hang time as I would finally drop back to earth. I was so good at this random exercise that at one point, that the University of Calgary track team coach asked me to return and demonstrate my prowess to the track team: what it looked like at its best.

It was moments like this that I used as a mental crutch to shore up my mental resolve during the coming months and years of failure and weakness. Without these occasional moments of brilliance, I would never have had the mental fortitude to survive the mind-numbing months of workouts and inconsistent or declining results.

Test #1 – Hard Training: F - Failure

Test #2 – Body Fat: F - Failure

Test #3: - VO2 Max: F - Failure

Test #4: - Max Squats: C - Average

Test #5: - Vertical Leap C - Average

Back in Colorado, training camp really was not going so well. After coming in with the highest of hopes and expectations, I was mentally and physically exhausted. Sadly, I had continually proved myself to be one of the weakest on the whole team. If it weren’t for these occasional moments where my specific and unique talents came to the fore, I probably would have been a mental basket case, but as it was I tried to stay confident and actually looked forward to the final test of the camp – Max Power Output - also known as the "Wingate Test."

Again, everyone seemed nervous about the test, but I think it was Bonnie Blair who said, “don’t worry Coyle – it’s a cycling test – it’ll be easy for you!” (Everyone seemed to think that anything on the bike would be easy for me, notwithstanding my last place finish on the VO2 test.)

As with the VO2 test, we received time slot assignments, and like before, I showed up to another low-lying barracks not far from the previous torture chamber on the OTC grounds. Like before there was a hallway to a small room with a stationary bike. Unlike before, the hallway was carpeted as was the room, and there were no big machines and only a few attendants, and no white lab coats. It was comforting at first until that first recoiling of my nostrils to the vague scent in the room – the unmistakable stench of vomit hidden under cleanser. Once again I got nervous – now what?

After I entered, one of the attendants asked me to get the seat height set up and make sure everything was comfortable. There was no eye contact. I did so. He then explained the nature of the test, “30 seconds with resistance, all out – as fast as you can go – got it? “Remember – hit it full out from ‘go’ else the test is wasted.”

I said “got it,” and got my feet cinched in good even as another technician began to turn the dial on the front of the flywheel while viewing his clipboard.

“All set,” he said, and then the first attendant said, “you might want to test the resistance…” Until this point I still had confidence. 30 seconds on a stationary bike with a flywheel to sending zinging – how hard could that be? Finally, something I’d be good at – a way to race my strengths instead of basting in my weaknesses.

A half second later a warm rush of terror caused a flush of sweat to appear on my arms and legs despite the dry air. When I pressed on the pedals, all that happened was that I stood up. I tried again – with my right leg in the two o’clock position I put my weight into the pedal and all that happened was that my body lifted from the seat.

“Um, I think the bike locked up,” I said.

“No no,” the two assured me in unison, and then one continued “just push real hard, and pull with the other leg – you’ve got 497 watts of resistance on due to the ratio with your weight so it’s a bit hard to get started.”

In disbelief I used all my might to push my right leg down while straining with my left hamstring to raise that leg. Immediately the wheel stopped. Suddenly the concept of 30 seconds became an eternity – to pedal THAT for a half minute! NO WAY! It was the approximate equivalent of finding the longest steepest (say, 15% grade) hill you've ever seen, and then sprinting up it from a dead stop in a big gear. This new news brought fear - real fear - out of every pore of my skin.

But they knew better than to let me think it over and suddenly in an official voice one was counting, “5, 4, 3, 2, 1, Go! GO! GO! GO!” And I drove my left quad (as my left foot was now in the up position) with all my might and convulsed my right hamstring to lift at the same time. Every tendon in my forarms stood out like razor blades, but, sure enough, the shiny chrome 50 lb flywheel began to turn, sluggishly at first, then building – 1, 2, 3 seconds passed by and I began to get inertia and rotational energy going. I moved out of the panic zone and began to really pedal and the two assistants continued, like me, to watch the seconds tick, and the RPM’s rise on the monitor.

Another second, and I began to enter the tiny realm of my little superpower: energy began crackling out of my legs and as, 4, 5, 6, seconds passed and my feet began to turn circles, spinning, then buzzing with a kind of manic yet fluid energy despite the heavy resistance: the shiny flywheel flew despite the band of resistance, and heat rose off of it releasing a new smell to the room.

I distinctly remember looking around the room at the astonished faces of the attendants as my feet hummed along and my rpms rocketed up 100, 140, 160, 180, 200, the bike vibrating the air and the floor as though I might lift off. Now, at 7 and 8 seconds, for once the faces were interested in something other than my failure. For the next two seconds, as heat continued to rise off the flywheel, I played roulette with my body having no idea what was to happen next.

How does that verse go? “Pride goes before….?”

9, seconds then 10... and my began feet slowing, just a little at first, but then dramatically as that humming energy faded to emptiness, 11, 12, 13 seconds, laboring, and the massive anaerobic effort suddenly began hitting my lungs and legs and brain all at the same time and a wave of paranoid fear rolled over me as the walls and ceiling of a tunnel of pain closed over my head.

I continued thrashing forward under the dark nape of fear, but all air was gone and the horizon continued to close as my lungs caught fire and my legs become molten lead.

Running out of air creates fear in one of its most raw, painful, debilitating forms – a deep inner panic that starts to simmer and boil over – to pervade everything – telling you to find a way to surface, to escape this intentional drowning. But there was no way out and like the VO2 test, the attendants were ready and had moved into a small semi-circle in front of the bars, “Keep it going! 14 seconds! … Halfway!” My legs had gone from 200 rpms down to 100rpms in 2 seconds. I was dying and there was no blood left in my whole body: it had been replaced by battery acid and fire erupted in every synapse. “16 seconds! 100% effort! You are on a good one!” they cried and suddenly their faces zoomed in and grew whiter even as an odd buzzing began.

Sixteen, seventeen, eighteen seconds and the dark tunnel I was in suddenly began to open and brighten and I began to hear a new sound: a wretched keening and rasping. It was me. I surprised myself with the volume and ugliness of the rattling, wheezing breaths that issued from my lungs. I tasted steel as my heart rate continued its climb; my blood scoured my veins and beat like a gong against my ear drums.

My laboring legs dropped to 80rpms, then 60 rpms. I had never felt pain this excruciating. “Nineteen, twenty, twenty-one seconds!” they screamed, the attendants were leaning in now, faces only inches from mine, shouting – yet sort of in slow motion, with fading sound – just movements and mouths and this ever building buzzing and brightening. I could feel my legs stopping altogether despite my concerted efforts to make them turn – but they no longer belonged to me – they belonged to the fire and the buzz of the fluorescent lights in the room.

I was strangely interested in how overexposed everything had become and even as I felt my legs stop and I looked up the crescendo came, a buzzing rotation up and over my head like a low flying airplane dropping a mesh of nausea. Everything turned white then yellow then black. Then it was quiet.

------------------

When I woke up, I was on a cot, in another room. Someone was touching my arm as I opened my eyes, “you are OK.” Another voice was squealing from another part of the room, in response to some ongoing dialog, “…yeah I know! But no one has ever passed out ON the bike before!”

I was disgusted. I got up, woozy, and hands steadied me. Voices seemed to be indicating success (like last time after the V02) but I couldn’t wait to get away. They continued their monologue with something about peak power and rapid decline but I thought to myself with contempt, “here’s the final test – the one I thought I’d finally get some results worth having. “Instead, I barely finished half the test without passing out. “I suck, I suck, I suck, I suck…” Over and over those were the words my pedals repeated as I rode back for the dorms.

When the manila envelopes were passed out that evening again under the door, I didn’t bother to open mine for a while. Finally, when no one else was around, I lifted the flap to my reality – it looked like this:

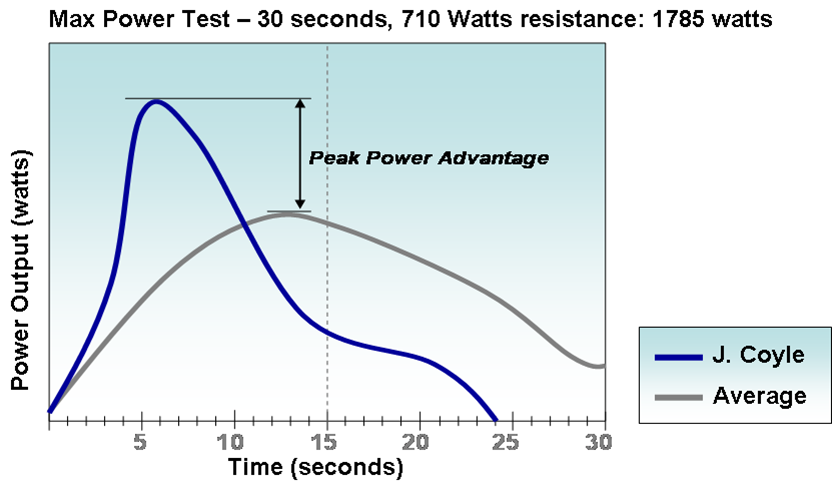

At my peak power, I had produced 23.1 watts/kilo and a peak power 1785 watts – the highest of the team regardless of weight. Unfortunately, as the doctor who reviewed my chart with me noted, “you also have the highest rate of decline of anyone on the team.” Thanks doc, for pointing out the obvious.

Here was the clincher for me – if the shortest event in speedskating lasts about 36 seconds – how is it possible I could ever hope to be good at the sport?

Yet, as I reminded myself, I already had been. I had been quite good – even at events lasting 2, 3, even 7 minutes…

In hindsight, this was an absolutely compelling piece of data to use to my advantage – it really merely informed what I should have already known – than in situations that called for short bursts of power, I had a natural advantage. It didn’t occur to me that this strength could be used and repeated with recovery in intervals – instead I merely considered the fact that I was apparently only competitive in events lasting less than 15 seconds, and it immediately came to mind that the shortest event in speedskating, the 500 meters, lasts somewhere around 35-40 seconds. So I decided, once again, to ignore this data.

Test #1 – Hard Training: F - Failure

Test #2 – Body Fat: F - Failure

Test #3: - VO2 Max: F - Failure

Test #4: - Max Squats: C - Average

Test #5: - Vertical Leap C - Average

Test #6: - Max Power F - Failure

Attached below is a pair of video segments that paints a clear picture of what the test show – and what I should have already known – that my talents are in the realm of accelerations with limited duration.

Both videos are from the 1986 North American Short Track Championships – Intermediate division 500m final (the highest level of competition at that time for ages 18 and under).

The first video shows my strengths in all their short lived glory – sprinting from lane 5 into the lead and extending it quickly over the next 10 seconds. As Marcus Buckingham or Mike Walden would say – “race your strengths.” Again – here is the definition:

“The definition of strength is quite specific: consistent near perfect performance in an activity.”

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0EqcDkeCZCw]

This would be my strength. In all my years of short track I could usually win the start – no matter the lane.

The second video shows my weakness – the remainder of the race – this snippet is the last half of that same race. I did end up winning – but just barely:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QhGfGzeXAQ8]

It is obvious now, but really I didn’t see these obvious talents and challenges back then, and frankly, coaches just wanted to train those weaknesses out of me – but that approach never worked - though I certainly tried. Instead, what did work was for me to put my strengths to work in unique and sometimes subtle ways - as Walden always knew... But that is a topic for Vol. 4.

Marcus Buckingham again, "Each person's greatest room for growth is in the areas of his or her greatest strength. "You will excel only by maximizing your strengths, not by fixing your weaknesses."

Next Up: Vol 4. Ignoring good advice and Racing my Strengths