Vancouver Journal #13: Beginnings and Endings

Vancouver Journal #13: Beginnings and Endings What spark might cause a little girl to aspire to something great? What magic mixture of activities, encouragement, talent and belief combine to ignite the passion and perseverance required to become an “outlier” like an Olympic athlete?

Endings Part 1: We knew it was over before we saw it onscreen by the thunderous roar coming from the stadium. I am a speedskater, but, sitting outside of the closing ceremonies venue (BC Place), watching the Canada - USA gold medal hockey match on TV in the NBC commissary I couldn’t help be enthralled by the drama. The game, which had entered sudden death overtime, was being played in a venue a few hundred feet away, but was on a brief tape delay. Moments after the thunder from the stadium began, USA goalie Ryan Miller slumped face first onto the ice, puck in the net behind him and a whole city – a whole nation - celebrated. I was happy for Canada I guess. For the U.S. it was just another medal, for Canada, it was a matter of national pride. Besides, I wanted to enjoy my final night in Vancouver.

It was the last evening of the Olympics, one last night, one last hurrah for the world’s biggest party. A few hours later I entered the stadium hosting the closing ceremonies where I would fulfill my final duties for NBC as a “spotter.” I stayed busy finding athletes for interviews and the ceremonies were of a blur until the lights dimmed and Neil Young came onstage. His voice quavered as the torch flickered and went out, and I felt a sudden rush of coldness wash over me – it really was over - tomorrow, reality would resume…

This feeling, however, was nothing in comparison to another ending exactly 12 years earlier, when friend, competitor and part time announcer Chris Needham announced my retirement from the sport of speedskating. During my time in Vancouver, I was acutely aware that many of the athletes I was spending time with were about to undergo this same transition – Ian had declared his retirement from speedskating a few months prior, and Nick Pearson announced his the day of his 7th place finish in the 1000m.

Chris Needham was here as well, having made his own declaration of retirement from the sport just a few months ago after his own failed Olympic bid, and then there was Alex. Alex Izykowski was a boy of 11 when I was lucky enough to put my medal around his neck at Steamer’s pub in Bay City Michigan. He was 23 when we reconnected after his bronze medal in Torino, and now at 27 we have become great friends. Alex was training for this – what was to be his second Olympic games - when a series of misfortunes struck; back problems emerged interrupting his training, and then, last February Alex was struck by a car while biking through an intersection on a training ride and a few torturous months later he too announced his retirement from the sport.

Chris Needham was here as well, having made his own declaration of retirement from the sport just a few months ago after his own failed Olympic bid, and then there was Alex. Alex Izykowski was a boy of 11 when I was lucky enough to put my medal around his neck at Steamer’s pub in Bay City Michigan. He was 23 when we reconnected after his bronze medal in Torino, and now at 27 we have become great friends. Alex was training for this – what was to be his second Olympic games - when a series of misfortunes struck; back problems emerged interrupting his training, and then, last February Alex was struck by a car while biking through an intersection on a training ride and a few torturous months later he too announced his retirement from the sport.

Like me, each one of these athletes had spent more than a decade pursuing a dream, and like me, none of them quite reached their ultimate goal. As athletes aspiring to become Olympians, the mindset is ever one of “never give up, never give in,” and the Olympic dream becomes the North Star that directs and sustains through the suffering over the years. To suddenly extinguish that light is to give up on a belief, and for a great number of serious athletes, the transition to “reality” can be cold, empty, and directionless.

To say I was devastated when I failed at my second Olympic bid and decided to retire would be an understatement.It took me 8 years, and the inspiring words of a concerned parent – Alex’s father – before I truly transitioned from athlete to Olympian. I hoped I could return the favor for Alex in much shorter order.

----------------

Beginnings: Shannon and Katelina arrived the night before the opening ceremonies, or rather early the morning of. They were supposed to arrive at 1am, but flight delays and customs meant that they walked out of the terminal at 3:30am PST (5:30CST) and were exhausted.

Katelina is a sweet and senstitive nine year old girl. She reminds me of myself at that age: slight of build, innocent of the world, and mostly quiet and shy with periods of intensity that speak to untapped inner drives and motivations. At that age I was one year away from hating speedskating. Kat already hates it – or at least she hates the racing part… I was hoping that being at the Olympics might provide a spark of interest in sports for her.

The good news was I had managed to locate opening ceremonies tickets. In order to purchase tickets, weeks ago I had completed my taxes the very same day I received my tax documents, and I received my refund the same morning of opening ceremonies. I now had the money and had found available tickets - timing was serendipitous. Still, spending serious dollars just to watch a torch being lit?

------------------

Talent: I have read a host of books on psychology, training, rational vs. irrational thought, happiness, strengths, and talent over the past couple of years. I’m probably somewhat of an expert on the data available in this field, but that doesn’t mean I’m an apt practitioner. To date my daughter holds speedskating races with only slightly less contempt than math classes at school. Speaking with the other parents in the USA house made it easy to confirm: more often then not, the offspring of Olympians prefer NOT to follow the same dream as their parents. Conversely, most of these parents were just like me growing up – clueless and normal… until one day…

Daniel Coyle, author, talent expert and no relation, dug deep on talent development in his highly recommended book “The Talent Code.” He expertly uses the latest neuroscience along with anecdotal and statistical data to show what most “outliers” have in common when it comes to excellence. Specifically he finds that it is the passion to pursue “deep practice” of an activity over a period of years despite the suffering it involves. This deep practice causes “myelination” – the wrapping of electric circuits in the brain that then surface as “talent.”

Daniel clearly shows how hotbeds of talent around the globe have arisen where the suffering required for “deep practice” is overcome and fueled by a concept he calls “ignition.”

----------------

We filed into the stadium and I had no idea what to expect except that it “will be great.” It was a significant investment and I was nervous. Then it started. The lights dimmed, the crowd of 60,000 in white fell into a hush, and then a snowboarder shot down a ramp from the top of the stadium, off of a jump through the Olympic rings, and with an explosion of sound and fireworks, the opening ceremonies began.

The anthems, the singers, the lights and colors were an amazing spectacle, but through it all I was watching other eyes – I was watching Katelina. Despite an earlier pronouncement of “It sounds boring, I don’t want to go papa,” she was enthralled – eyes wide open, transfixed by the pageantry of the ceremonies - here she was, watching one of the world’s great shows preceding one of the world’s great competitive dramas. She swung her flashlights of different colors, banged on her blue cardboard drum (which became important for other reasons), watched skiers and snowboarders drop from the sky, ballet dancers pirouette onstage, a gigantic glowing polar bear rise from the floor, and a massive torch being lit. Our excellent seats were also right next to the athlete section, so I was able to point out a few Olympians I knew as well. The three hours flew by in minutes and she sat up, leaning forward throughout the entire show.

The anthems, the singers, the lights and colors were an amazing spectacle, but through it all I was watching other eyes – I was watching Katelina. Despite an earlier pronouncement of “It sounds boring, I don’t want to go papa,” she was enthralled – eyes wide open, transfixed by the pageantry of the ceremonies - here she was, watching one of the world’s great shows preceding one of the world’s great competitive dramas. She swung her flashlights of different colors, banged on her blue cardboard drum (which became important for other reasons), watched skiers and snowboarders drop from the sky, ballet dancers pirouette onstage, a gigantic glowing polar bear rise from the floor, and a massive torch being lit. Our excellent seats were also right next to the athlete section, so I was able to point out a few Olympians I knew as well. The three hours flew by in minutes and she sat up, leaning forward throughout the entire show.

-------------------

Ignition: Why would anyone begin this irrational behavior of training for the Olympics? I say irrational because any rational analysis of the situation must include odds and outcomes. The odds for anyone to become one of the few hundred athletes at the Olympic Games are very, very low, and the odds of earning a Olympic medal are even slimmer. The silver medal we earned in 1994? In the nearly 100 years of the modern Olympic games and thousands upon thousands of athletes and competitions it was only the 52nd Winter Olympics medal ever awarded to an athlete from the United States.

Then there is the barrier of outcomes. The expected outcome for newcomer in any sport with a skill element tends to start as “poor”. In my very first speed skating race of three laps, I got lapped – meaning the leaders passed me on their third lap as I was finishing my second. I was embarrassed, horrified and 10 years old. I cried… and cried some more. I demanded to never go again to that rink (Farwell field) I demanded to never skate again, I demanded all kinds of things, but parental relationships were different then: my dad consoled me – I’m sure of that – but he also had the power to decide for me. We returned again and again and it wasn’t an option - thus incredible importance of parents. And then someone who didn’t need to helped me (Jeanne Omelenchuk) http://johnkcoyle.wordpress.com/2008/02/08/jeanne-omelenchuk and I got better at it, but I wasn’t yet “lit” for skating – that came later at the hands of Marc Affholter http://johnkcoyle.wordpress.com/2008/12/24/marc-affholter/

Ignition. Even more than the breakthroughs of myelin and “outliers” and deep practice, to me the concept of “ignition” is the real magic. Yes of course: if you suffer through 10 years of dedicated focus on a specific skill and have a reasonable level of genetic talent, odds are you can become great. Fine – but we have just described almost nobody.

What is the primary difference between the talented kid who plays ball, runs, or skates for a couple of years and then moves on, distracted by “life” and all its fruits vs. the kid who focuses and abandons many of the easy joys of day-top-day living, embraces the suffering, and hence, in many cases, becomes “great.”? What makes a Bonnie Blair? A Katherine Reutter?

We know from science that repeated contact with a subject matter, a sport, instrument, or topic causes myelination – even if it is somewhat “accidental.” Over the years, circuits are developed that may lie somewhat dormant, and then, one day, through the right words, images, or circumstances, they are called upon. When this miracle of timing, confidence, and latent skill presents itself, the audience perceives “talent” and accolades suddenly form to support the activity and then “ignition” might occur.

For me it happened when I was eight years old. I was just a normal kid doing normal kid things. Then my dad bought me a bike and I started doing longer and longer bike tours with him. I didn’t know I was wrapping myelin around my circuits, strengthening the electrical impulses twitching the fibers in my mind and legs. If I was a harp, I was being strung and tuned, fiber by fiber, chord by chord. My father, like most parents, was the craftsman and tuner, and the chords were the series of 100 mile “century” rides I participated in before my 9th birthday… But the craftsman and the harpist have different roles, and more often than not, it is the expert touch of an outside hand that pulls those first pure notes from the instrument. For me, the hand whose resonant touch first activated those circuits belonged to a passing cyclist named Clair Young. http://johnkcoyle.wordpress.com/2008/10/16/clair-young/ Suddenly I had a label. I was a “bike rider.” I said it in my head a dozen times before I said it aloud. For an 11 year old Alex Izykowski, it was the weight of an Olympic silver medal around his neck. For Meryl Davis or at least her mother, it was the realization that “if my neighbors can do this, we can do it too…”

If building experience and skill is the kindling and logs for a fire, the moment of ignition is the match. Without the match, all that preparation goes to waste. But how to light that fire? Dozens of books on psychology, training, strengths focus, neuroscience, and happiness later, and I still haven’t figured it all out, though I do have some hypotheses. What appears to have happened in each of these cases is the neuropsychological phenomena of “irrational belief” overcoming “rational thought.” More specifically it is that those athletes (and musicians and other paragons of achievement) move from “I think I can” to “(I know) I can.” And in the process of removing “I think” they have invoked belief; that irrational process that does not rely on day-to-day facts and data and instead can weather the vagaries of the day-to-day failures inherent in the pursuit of something difficult – and great.

What is belief anyway? Daniel Coyle, Malcolm Gladwell, and others have built a great case for how this mysterious substance of myelin – the gray matter of the brain – wraps neurons and can speed the processing time through the neural substrate by 1000X and hence accelerate well past the time required for “rational thought.” At its best, this myelination results in “automaticity” whereupon rational thought isn’t even required and the action becomes “instinctive” and hence gets labeled as “talent.” Tiger Woods and John McEnroe are great examples of this – trained since they were little kids they developed skill circuits beyond the levels of anyone in their game. But why did they bother to do it? They could have rebelled, could have quit.

I’ll be honest, I have no idea how ignition works. My daughter pretty much hates the idea of racing – but that is likely due to the fact that the few times she has raced, she did not win. I think I have done a decent job of helping her build skill in the areas of skating and cycling without the undue pressure of competition when she’s not yet ready (she can’t win, so for her, she’d just rather not compete - a feeling I understand completely…)

I would love for Katelina to someday have the kinds of opportunities that I have been so blessed with through my pursuit of excellence through sport… It doesn't have to be speedskating or cycling - really it doesn't have to be sport at all. Mostly I want her to feel the positivity, direction and camaraderie shared when a group of people take on big risks for big rewards. But how? How can I as a parent help create the kindling and fuel that might someday be lit? How do I keep it fun and remove the kind of pressure to achieve that causes so many kids to rebel and quit? I worry and worry about this and grasp for answers…

---------------------

Endings Part 2: Vancouver City was described as “No Fun-couver” by its residents prior to the Olympics, and they were reticent or anxious in their unique Canadian way about the arrival of the Olympics before the start of the games. The costs, the traffic, logistics and security issues had put the local citizenship on guard… Then the torch arrived and overnight this relatively sleepy large city became party-central for the world. In speaking with tenured NBC staff and support personnel, it seems the unanimous opinion is that Vancouver truly has become the world’s best 17 day party - ever.

Earlier on the day of closing ceremonies, I was walking down Grandview by Robson (the Olympic “main drag) on the way to a meeting when I first saw them – a group of 7 or 8 young male Canadians clad in bright red body paint including their faces and hair, flags as capes, and little else other than shorts despite the 50 degree weather. “CAN-A-DA! CAN-A-DA! CANADA!”. It was only noon, but by their ragged chanting and singing it seemed likely that no small amount of Canadian beer was involved in their festivities.

There was nothing particularly unusual about passing a loud group of brightly painted, underdressed and intoxicated Canadian men - this had been par for the course for two weeks now except that A) in one hour one of the main events of the games was to start – the USA – Canada hockey showdown just few blocks away, and B) I had just overtaken 6 or 7 guys similarly underdressed, but with blue face paint and American flags chanting “USA, USA, USA!” and they were just behind me and heading this direction.

I was already at risk of being late, but I had to slow and watch the inevitable train wreck to follow as both parties had now seen each other. The chants grew more fervent and the pace picked up, and I watched the aggressive acceleration of alcohol fueled nationalism streak towards each other, their roars and chanting reaching a fever pitch. Then, like a scene from Braveheart where the Irish and Scots meet mid-battlefield the two groups suddenly slowed and came abreast. Much like a post-game hockey lineup each “team” passed by with high fives and genuine smiles before continuing their respective marches.

-----------------

After closing ceremonies finished I stopped by the USA house, but it was empty - no more medals to be awarded and most of my old and new friends already en-route for home. I left and walked one last time down Grandview and there at least the party was still on. Throngs of Canadians were celebrating the hockey win, and their best Olympics medal count ever.

As I walked back to the hotel, I passed a couple wearing USA gear. They were dodging the craziness just as I was. They smiled ruefully at me and said “I guess we should be glad they won or this walk might be more difficult.” I nodded in agreement and continued on to my hotel to pack. As I folded up my bike and stuffed my clothes into my suitcase I reflected on the previous 20 days while saving the most important items to pack for last.

A few days prior, alone for a few moments at the USA house, I looked over at Alex and asked him whether being at the Olympics as an Olympian vs. and athlete was difficult and how he was feeling about it. He turned to me, paused, and then with real clarity said something along these lines, "To be honest, I feel more blessed and lucky now - by far - than I ever did as an athlete or in Torino."

I knew exactly how he felt.

My bike and bags were packed and it was time for my 3am pickup to head to the airport. I just had one final item to put in my carry-on where it would be guaranteed to arrive home safely. This blue octagon and “Sharpie” pen had been my companions for the last week, packed safely in my backpack wherever I went. It was the cardboard drum from opening ceremonies – nothing particularly special in and of itself. But inside, I had collected the pins and tickets and keepsakes from the games for Katelina – as a scrapbook and memoir from her trip.

My bike and bags were packed and it was time for my 3am pickup to head to the airport. I just had one final item to put in my carry-on where it would be guaranteed to arrive home safely. This blue octagon and “Sharpie” pen had been my companions for the last week, packed safely in my backpack wherever I went. It was the cardboard drum from opening ceremonies – nothing particularly special in and of itself. But inside, I had collected the pins and tickets and keepsakes from the games for Katelina – as a scrapbook and memoir from her trip.

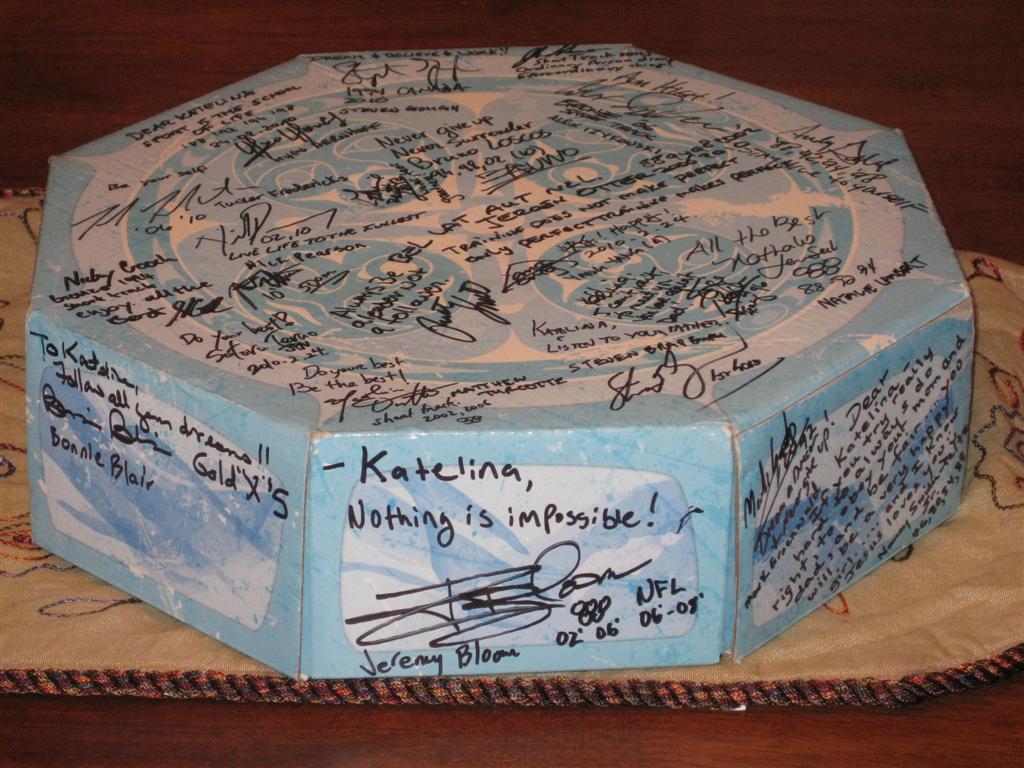

Perhaps more importantly, on the outside I had managed to gather, over the past week, dozens of signatures and inscriptions from Olympians and medalists from all over the world. Specifically I had asked each one to sign their name, and then write one short piece of advice for my nine year old daughter. This, oddly, proved a daunting task for these exceptional people, but everyone obliged in the end, and I carefully packed it, along with “Quatchie” – one of the Olympic mascots – into my bag and headed for the lobby – and for home.

Postscript: Last night, two weeks after my return, we took Katelina and a friend up to the Petit Center in Milwaukee – a U.S. Olympic training site, and one of only two covered Olympic size long track rinks in the country. Normally she has greeted weekly practice with disdain, but last night she couldn’t get her skates on fast enough, and immediately took off in a blaze of speed, blond tresses flying behind her. Flushed with excitement she did lap after lap on her own, wearing her little Polo USA jacket and long bladed speedskates. A half dozen kids stopped her to talk to her about her skates or how fast she was going, and breathlessly she related her excitement on the ride home. Two hours and 27 laps later (almost 8 miles) it was time to go.

“Papa,” she told me, “This man, a boy, and a couple little girls asked me how I could go so fast” she spoke quickly as she often does when she’s excited.

“What did you say?” I asked.

“Papa, I told him - I told him I could go this fast because I’m a speedskater!” she said with emphasis. My smile grew and grew.

Ignition often starts with a label: “I am a ___________”